By Nkunimdini ASANTE-ANTWI

If a person is of sound mind, then it is far from their intention to oppose the Bank of Ghana’s initiatives to reform the microfinance sector in Ghana, as this sector suffers from numerous problems and urgent treatment is necessary.

For many years, the private sector has continuously criticized the extremely high lending rates within the banking industry, attributing these to the persistently low levels of investment in non-current assets, which are essential for enhancing market competitiveness.

In the microfinance industry, interest rates are even more problematic, to the extent that they are less severe than the harsh lending practices seen in medieval Europe, which led Pope Clement V to impose a prohibition in 1311 AD.

In today’s microfinance landscape, it’s not unusual to encounter a lender imposing monthly interest rates ranging from 10-12%. Indeed, you could even come across rates as high as 15% per month. If this doesn’t raise any ethical concerns, maybe a specific example will awaken your sense of right and wrong.

Suppose Aunty YaaYaa, who sells tomatoes at Agbogbloshie, takes out a loan of GH¢4000 for three months with an interest rate of 12%, and reuses the borrowed money four times throughout the year. In this case, she ends up paying GH5,760 in interest costs, which is 44% more than the original loan amount.

Individuals who support the existing system often use frequently mentioned arguments like high borrowing costs, high operational expenses, and so on, as if decisions about business model design are fixed. Some critics have humorously claimed that modern microfinance, as it is currently implemented in Ghana, is merely economic and organized crime disguised as financial inclusion.

They make light-hearted remarks, saying, “if this is what is referred to as financial inclusion, then may we all remain excluded.” There is no doubt that policymakers are dealing with a textbook example of market failure. The claim that microfinance, as it is currently implemented, represents ‘mission drift’ is a valid criticism—guilty as charged, in essence. Several questions then come to mind:

- What type of microfinance environment do we aim to develop as a nation? What policy results should sector reforms achieve? In short, what changes should take place?

- What potential dangers might hinder this reform initiative, considering both its planning and execution?

- What particular actions, if any, might reduce the dangers during the execution of the program?

This piece aims to present certain viewpoints regarding the aforementioned questions.

Question 1: What form should “change” take?It’s a common saying that effective policy-making should be based on solid analysis. It’s reasonable to state that the Bank of Ghana’s reform initiative so far has been quite comprehensive and thought-provoking. As per the publications from the Central Bank, there are at least 5 factors contributing to the weaknesses found in microfinance institutions:

- Undercapitalization

- Weak governance practices

- Weak internal controls

- Failure to absorb shocks (weak financial positions)

- High market fragmentation

If I may be so courageous as to add to the list, I would mention poorly structured business models, which ultimately result in high operational costs, which in turn cause inflated loan rates. The valuation of financial assets is influenced by various factors, some of which are external.

The pricing mechanism typically considers at least four elements: cost of funding, opportunity cost, operational expenses, and risk premium. With the exception of opportunity cost, the remaining factors are variables that can be controlled by management.

This essentially implies that if the Board and senior management are determined to create an effective operational structure, it could enhance the chances of controlling expenses, and any resulting cost reductions might be transferred to customers.

More easily stated than accomplished, yet it requires strong corporate governance, effective internal controls, comprehensive enterprise risk management, and a proactive internal audit process, meaning a properly operating three-line-of-defence framework.

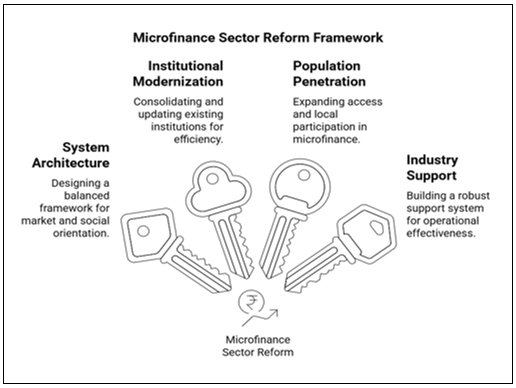

It is encouraging, therefore, to observe that the Bank of Ghana’s proposed reform plan aligns with this global perspective. As stated by the Bank, the upcoming Microfinance reform will be based on four strategic themes:

- Pillar 1: Create a system architectural structure that integrates market-driven strategies with a socially focused approach to cater to various groups of customers.

- Pillar 2: Promote the integration and updating of current organizations to enhance effectiveness.

- Pillar 3: Encourage widespread community involvement and foster local engagement and commitment.

- Pillar 4: Establish a sector-wide support framework to improve operational assistance, oversight efficiency, and policy dissemination.

In the end, the reform must showcase clear social and economic advantages for those who use financial services. This involves (a) a structured elimination of excessive interest rates, (b) enhanced service standards, and (c) a wider range of product choices.

Question 2: What are the potential dangers related to the design and execution of the program?Based on the strategic themes of the reform, I identify two sets of risks. Firstly, I anticipate a growing opposition to the concept of mergers and acquisitions, which could be influenced by the regulator.

If the reformers choose to establish a new minimum paid-up capital of, for example, GH¢40 million for Microfinance Banks, and GH¢30 million for Community Banks, it would be logical for providers to explore Mergers and Acquisitions as a feasible way to meet these requirements.

Regrettably, I don’t anticipate many mergers and acquisitions taking place. There’s a justification for my skepticism. I remember that before 2017, after the Bank increased its minimum paid-up capital to GH¢400 million, the regulator applied moral persuasion to urge banks that failed to meet the requirement to collaborate. The reaction? Silent objections and confidential requests. The rest is history.

Within less than a decade, we have returned to the same crossroads. Therefore, no, I don’t anticipate any dynamic market-driven merger and acquisition activity that would promote sector consolidation, as the regulator hopes. Rather, I foresee two developments. Firstly, among MFIs with net own funds under GH¢15 million, there will be an institutional departure; a widespread self-classification into the category of regulated microfinance institutions known as Last Mile Providers.

Secondly, MFIs with net-own funds exceeding GH¢15 million, and/or those with substantial access to the capital market, whether via private placements or public offerings, might withstand any grace period that the regulator may provide, in an effort to secure the necessary capital. In the end, water will flow where it can accumulate.

The risk I observe, however, which is connected to the concept of self-relegation, is the issue of regulatory arbitrage. Let me clarify: All Specialized Deposit-taking Institutions (Tier 1, Tier 2, or even Tier 3) have regulatory compliance requirements that are significantly different from those that, for example, a Tier 4 operator must adhere to.

For example: the Corporate Governance Directive, 2018 requires Tier 1-3 license holders to perform an annual Board self-assessment. Question: Can a Tier 2 Microfinance company that classifies itself as a Last-Mile Provider choose to re-register the business as a sole proprietorship to escape excessive regulatory demands? This query is not only valid, but without explicit and clear guidelines, this situation might actually occur.

Here are my concluding remarks:

- Interest rates in the MFI sector are exploitative. Although direct price controls are an inappropriate policy measure in a market-driven economy, the regulator should use alternative market-oriented strategies to discourage excessive interest rates. Unfortunately, the act of providing Pre-agreement disclosure statements as required by Section 57 of the Borrowers and Lenders Act, 2020 (Act 1052) has not achieved the desired beneficial impact on loan charges. More practical measures need to be explored.

- The BoG should work together with the SEC and the Ghana Stock Exchange to develop a rapid public listing plan for MFIs that are interested in securing additional capital via an IPO.

- A limited time period to meet the updated capital requirements must be provided, but only under stringent conditions:

- Organizations are required to present realistic capital strategies that show adherence within a specified timeframe.

- Organizations that have deficiencies in their corporate governance structure are required to present business plans outlining a strategy to achieve 3-lines-of-defence maturity within a specified timeframe.

- The Bank of Ghana needs to be cautious to prevent the regulatory errors observed during the 2017 financial sector cleanup. Some of the stakeholder discussions that will go along with this reform should aim to comfort the market by showing that the present insolvency resolution system has been improved based on insights gained from previous errors.

The writer is a fellow at Yieldera Policy Institute, a research organization dedicated to the financial industry. He also established Metis Decisions Limited, a management consulting company that focuses on strategy, governance, and risk advisory services. Seehttp://metisdecisions.com | Phone: 0242564143

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc.Syndigate.info).